About five years ago, trainer Kristin Pokluda, of Whitesboro, Texas took six horses to her veterinarian’s free ulcer screenings. All six had ulcers.

“I’ve spent a lot of time learning how to manage them. By making changes I’ve been able to significantly reduce the number of horses in my barn that have them,” she said. “Every new horse that comes into the barn gets screened and treated as needed.”

Pokluda is not alone. Research shows that more than half of competitive horses likely have ulcers. In Thoroughbred racehorses that figure can be as high as 70 to 90 percent.

“Ulcers are more common than people think they are,” said Dr. Sherry Johnson, a veterinarian at Equine Sports Medicine, LLC. The sports medicine practice based out of Pilot Point, Texas, provides care to horses in major competitions across various sanctions including the American Quarter Horse Association (AQHA), American Paint Horse Association (APHA) and National Snaffle Bit Association (NSBA) World Championship Shows among others.

“The interesting thing about this disease is that it seems to be affected by the environmental stressors,” Dr. Johnson said. “Management, stress levels and even housing conditions have been shown in literature to be associated with a horse’s chances of developing ulcers.”

Show horses are prime candidates for ulcers because exercise, stress and travel are proven risk factors. Ulcers can be extremely painful, especially when left untreated. When Kate Workman, a veterinarian at Hassinger Equine Service and Rehabilitation, the show veterinarian for many of the east coast’s largest events, began working on the show circuit she was surprised by the number of horses with acute colic episodes that were later diagnosed with ulcers.

“I used to think of ulcers being a more subtle chronic change but they can most certainly have flare ups that cause a sudden increase in pain,” she said.

Pokluda believes that part of the reason the trainers and owners misjudge the severity of ulcers is because the tissue damage isn’t visible and the symptoms not always obvious.

“When a horse has a major injury to someplace like its neck, it’s automatically fixed because it’s visible,” said Pokluda. “We can’t see the stomach so it’s easy not to think about it. If people could see what happens to the stomach, everyone would take the time and make the investment to fix it.”

Although ulcers themselves may not be noticeable and the symptoms elusive, this is one disease that trainers and owners can directly eliminate or contribute to.

“Ulcers are not a naturally occurring condition,” explained Ben Sykes an associate professor at The University of Queensland Australia School of Veterinary Sciences. He is an international expert and researcher who focuses on ulcers. “The condition is directly related to domestication and management.”

To reduce a horse’s chances for developing ulcers, it’s important to know how the horse’s stomach functions and understand what management practices can contribute to their development.

UNDERSTANDING ULCERS

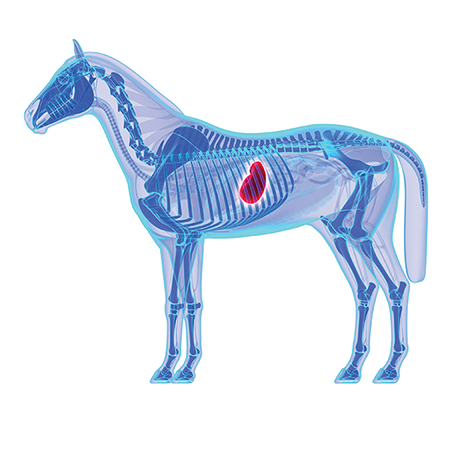

A horse’s stomach is designed to slowly consume forage throughout the day. As forage is eaten, the stomach continuously releases acid to help with digestion, explained Dr. Workman. When gastric acid builds up in the stomach it can damage the stomach lining and cause pain.

For years, ulcers were broadly called Equine Gastric Ulcer Syndrome (EGUS). Recent research has described that there are actually two forms of gastric ulcerations with differing risk factors and treatments.

The most common occurs in the non-glandular, top portion of the stomach and is called Equine Squamous Gastric Disease (ESGD). Dr. Sykes likened ESGD to the feelings of heartburn. In mild cases, horses likely feel a reflux-like discomfort that is caused by excess acid production, while more severe clinical signs may be present in some cases.

When the stomach is empty, there isn’t a buffer from the stomach juices. That acid build-up over time contributes to the development of squamous ulcers.

“These are the ulcers that people classically think of,” Dr. Workman said. “These ulcers are often easily treated with a medication called omeprazole.”

Competitive horses are more likely to have ESGD than their recreational counterparts. Research findings show that exercise and management increase a horse’s chances for developing ulcers in this region of the stomach.

“Risk and disease severity increase as the intensity of feeding and exercise increases,” Dr Sykes said. “In the western horse population around 50 percent of horses would be expected to have some degree of ESGD. This does not mean that 50 percent of horses will have clinical signs, rather it is based on endoscopic studies of stomachs.”

Horses can also have erosions or ulcerations in the glandular or lower portions of their stomachs. This is called Equine Glandular Gastric Disease (EGGD). These are much more difficult to treat and typically require a combination of medications given over longer periods of time, according to Dr. Workman.

“EGGD prevalence is less well documented and to my knowledge no-one has specifically reported the western horse population to date,” said Dr. Sykes. “Based on other populations we’d expect it to be around the 50 percent mark.”

Surprisingly, EGGD has been observed in horses not typically associated with risk factors for squamous ulcers. Horses that live “good lifestyles” with ample turnout, little exercise and free access to forage still have a high prevalence of glandular disease.

The risk factors, symptoms and treatment protocol for ESGD and EGGD are dramatically different. That makes diagnosis critical to developing a treatment plan and long-term management strategies.

“With this in mind, appropriate investigation of any horse with clinical suspicion of EGUS is warranted,” said Dr. Sykes.

SYMPTOMS AND DIAGNOSIS

Nervousness, cinchiness, poor coat condition and diarrhea are the most readily promoted symptoms of ulcers. But Pokluda said that the only clear sign was in horses that didn’t gain weight easily. There weren’t other outward signs that her horses were uncomfortable.

“What surprised me the most was that the more anxious horses that I would have thought had ulcers did not. The quieter ones that I wouldn’t have suspected of having ulcers, had them,” she said.

The most common complaint Dr. Johnson hears from clients is their horse just doesn’t seem right. Watching a horse closely for subtle behavior changes can provide important clues. For example, Dr. Johnson always tries to observe a horse’s eating habits. At feeding time a horse with ulcers tends to go right after its hay or grain like any normal horse, but then may quit eating and stand at the back of the stall.

“It takes 10 to 15 minutes for that acid to get going,” she said. “Once the acid secretion increases, it can become painful and lead to an abnormal appetite.”

Overall, Dr Sykes agrees that unexplained weight loss is the most common clinical sign at a population level, although individual horses may show a wide range of clinical signs. One of Dr. Sykes’ clients had a horse that randomly began dunking its hay. The horseman claimed the horse had never done that before. Turns out the horse had ulcers.

Colic, especially around times of competition and transport, can also be an indication of ulcers. Dr. Johnson recounted one frustrating experience with a performance halter horse. The horse had no problems at home. But as soon as the mare arrived at a show, she would begin to exhibit colic signs such as pawing, rolling and an elevated heart rate.

“We’d give her fluids, do bloodwork, I’d palpate the horse rectally and eventually the signs would resolve with supportive care,” Dr. Johnson said. “It became this consistent joke that I’d see her at the next show.”

After the third show, Dr. Johnson referred the client for further evaluation at a referral center. The horse was scoped and diagnosed with ulcers and a full workup showed no other problems.

“It’s important to consider that ulcers may be contributing to other issues like colic,” she said.

The only surefire way to diagnose ulcers is to pass a small camera through the horse’s nose through its esophagus and into the stomach through a procedure called endoscopy. The endoscope’s images capture ulcerations within the horse’s stomach. Horses must be fasted prior to the procedure and that’s not always feasible in show horses.

“Sometimes we have clients try a prophylactic course of omeprazole to see if any improvements are made,” Dr. Johnson said. “If they show improvement then we’ll move forward with a treatment plan or more diagnostics such as a gastroscopy.”

Gastrocopy is the preferred diagnostic tool and it can be an expensive procedure. As Pokluda learned, it’s often covered by insurance. When she first started screening and treated horses, she and clients paid out of pocket because she believed it was worth the investment.

“It’s important to ask your insurance company if your current policy covers it,” she said. “It’s equally important to ask about if you’re researching new companies too.”

TREATMENT OF ULCERS

The way ulcers are treated depends on the type of ulcers the horse has. Oral omeprazole has been the go-to treatment for nearly two decades. The medication helps block the acid pumps in the stomach, which reduces the overall acid in the horse’s stomach, said Dr. Workman

“If a horse is diagnosed with ulcers, a 30-day treatment of omeprazole is often enough to cure the ulcers,” she said.

There is a big debate on which omeprazole products work for gastric ulcers. Gastrogard and Ulcergard are currently the only FDA approved medication for treatment of gastric ulcers in horses. There are other compounded products that have not yet been approved by the FDA.

“Some studies have shown that compounded omperazole products do not work as well as these FDA approved products,” she said. “However, more recent studies are showing the effects are more related to quality of product.”

Although both Gastrogard and Ulcergard are omeprazole-based paste products and are manufactured by the same company, they are not the same product. One is designed to treat ulcers (Gastrogard), the other to prevent them (Ulcergard).

The significant difference between FDA approved omeprazole and compounded products is the guarantee behind the amount of active drug in the dose and the length of time the medication will last in the horse’s system.

“Since Gastrogard is FDA tested, a tube of contains the precise amount of omperazole it claims to have. You do not have that guarantee from a compounded product,” Dr. Workman said. “Compounded products can work just as effectively, as long as they come from a quality supplier and contain active omeprazole.”

While there has been a lot of conversation about the compounded versus FDA approved omeprazole, there has been little attention paid to the impact of feeding on drug absorption and efficacy until recently, according to Dr. Sykes. It’s well known in other species that feeding reduces the absorption of omeprazole, and recent studies have shown the same thing in the horse.

“When compared with an overnight fast, free choice hay reduces the absorption of oral omeprazole by approximately one-half to two-thirds,” he said. “Similarly, when looking at stomach pH, the degree of demonstrable acid suppression markedly reduces when horses are eating free choice hay.”

This changes the way veterinarians think about giving oral omeprazole. The current recommendations are that it be administered after an overnight fast, and approximately 60 minutes before feeding, to maximize absorption and efficacy, he said.

Omeprazole is often recommended as a preventative in advance of a stress inducing event.

“I know some Halter folks that give Ulcergard to babies the day that they wean,” said Pokluda. “It’s the most stressful day in a horse’s life.”

She gives every horse in her barn Ulcergard prior to a show. Her philosophy is the prevention is less expensive than the cure and she feels confident that her horses are comfortable. While Ulcergard and Gastrogard are approved drugs in most associations, it’s not in all so it’s imperative to know your association’s rules. For example, Pokluda is able to use it when showing in AQHA and National Snaffle Bit Association (NSBA) events, but not Appaloosa Horse Club shows.

Dr. Sykes cautioned that there isn’t adequate scientific evidence that prevention doses are consistently effective when given alongside free choice hay, or that a specific, lower dose works for all situations. He encourages veterinarians and trainers alike to aim for the minimally effective dose based on the individual horse and its feeding.

In addition to omeprazole, feed and supplement manufacturers have developed daily formulations that may aid in maintaining a horse’s natural pH level and keep the mucosal lining healthier. For example, Purina’s Outlast and SmartPak’s Hindgut are two such products. But it’s important to remember that these products don’t heal ulcers. Once a horse has ulcers they need to be treated with medication.

In addition to omemprazole, other medications used in ulcer treatment include ranitidine, cimetidine, famotidine and sucralfate. Each has various mechanisms and may or may not work in certain ulcer scenarios. In the near future it is expected that a number of new, pharmacological treatment options for equine gastric ulcers will become available in the US market.

“These new treatment options will give veterinarians a broader range of options for managing EGUS. In particular, they will improve the management of refractory cases, and allow simplified treatment regimens removing the need to worry about the negative impact that feeding has on the absorption of oral omeprazole,” Dr Sykes said.

REDUCE THE CHANCE OF ULCERS

Since ulcers are a result of domestication and human interaction, the best way to prevent them is by being aware of the risk factors and implementing strategies to minimize them. Forage intake tops the list of ways to reduce a horse’s chance for squamous ulcers.

Alfalfa is touted as the hay of choice to prevent ulcers. However, Dr. Johnson emphasized that timing and quantity may be as important as variety.

Horses can develop ulcers within hours of being restricted from food, said Dr. Workman. If possible it is best to have free choice hay for them.

If a horse requires a lot of grain, she recommends feeding it over three to four meals rather than two larger meals.

“We can increase the period of time that stabled horses spend consuming roughage by providing multiple sites of forage,” said Dr. Sykes. “It has been shown that horses with multiple hay nets spend more time grazing than horses with a single forage site. This would be expected to increase the pH in the proximal stomach and further reduce the risk of ESGD compared with single hay net alone. Slow feeder hay nets may also be useful in some situations where total intake needs to be restricted but we still want to maximize the time spent eating.”

Interestingly, horses like people don’t eat after a certain point each night. They consume the majority of their roughage diet during the day and sleep at night. This may impact horses predisposed to ulcers who are turned out at night and stalled during the day if they don’t have access to a continuous hay supply inside.

Timing a horse’s forage intake can also be important. Dr. Sykes explained that when horses are fed in the morning there is often an increase in stomach pH associated with buffering from the feed and saliva. Research has shown a physical effect of the feed stopping acid from splashing around in the stomach.

“We can use this to reduce the risk of ESGD because if we exercise horses within the two hour window post feeding, especially of a roughage based meal, there is less acid in the stomach to splash around, and the physical presence of the feed makes it harder for splashing to occur,” he said.

Hay, or roughage in general, remains an important management tool for reducing ESGD risk. However, recognizing the influence exercise has on ulcer formation is equally important. Studies have shown a direct correlation between the frequency of exercise and the chances for developing ulcers, specifically those in the glandular region. Surprisingly, for the glandular region it’s unrelated to how hard the horse works, just how many days per week.

“Studies have shown that the risk of EGGD goes up with the number of days worked per week,” said Dr. Sykes. “With this in mind the current recommendation is that, to reduce the risk of EGGD, horses exercise no more than four to five days per week, with the remaining days set as dedicated rest days.”

And when it comes to rest, Dr. Johnson believes that means giving horses time away from their human handlers. She advises clients to give horses time away from people whether that’s while they are in their stall or on turnout.

“Horses need to decompress from us as much as we need time away from them,” she said.

The regular, long-term use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) can also increase a horse’s risk for developing ulcers. As such their use should always be under veterinary supervision to balance the risks and benefits for each individual horse.

Behavioral stress also appears to important factor for EGGD more than ESGD, Dr. Sykes added. To minimize a horse’s stress, he encourages several techniques that can help reduce a horse’s stress level.

First, is to create a regular schedule. That includes feeding time, turnout and training. Horses that are frequently hauled to shows have a less regular schedule. But by maintaining the same feeding and ride times to the extent possible while at the show can be helpful.

Second, he recommends co-habitation. Horses by nature are herd animals and socialization with other horses is critical to their well-being. Stalling or turning horses out next to other horses is better than isolation but isn’t the same as co-habitation. Horses benefit from interacting with other horses through grooming and other social rituals. At training barns, space and perceived risk of injury often prohibits this type of management, but Dr Sykes encourages horse owners and trainers to work towards addressing this important aspect of their care.

“With some time and patience, a suitable paddock mate can be found for most horses. It’s just a matter of finding the right personality mix” he said.

Finally, limiting the number of handlers and riders appear to be logical to reduce the risk of EGGD in pre-disposed horses.

“Paying attention to your horses and picking up on the little things sooner rather than later may give your horse the best outcomes for treatment and long-term management of ulcers,” Dr. Johnson concluded.

You must be logged in to post a comment Login