Among Quarter Horses and across many other disciplines and breeds, the most common cause of hind end lameness is arthritis of the lower hock joints.

Among Quarter Horses and across many other disciplines and breeds, the most common cause of hind end lameness is arthritis of the lower hock joints.

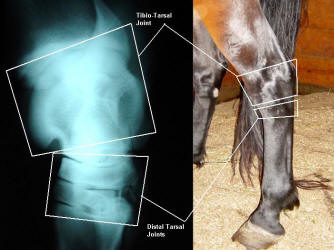

The hock is composed of multiple joints, including (from top to bottom) the tarsocrural and talocalcaneal joints, the proximal intertarsal joint, the distal intertarsal joint, and the tarsometatarsal joint. While arthritis can occur in any or all of these joints, by far the most commonly affected are the bottom two joints, the distal intertarsal and tarsometatarsal joints.

Because these joints function more through compression and rotation rather than flexion and extension, they are considered low motion joints (as opposed to the tarsocrural joint, which is responsible for the flexion and extension of the hock itself).

Potential causes of lower hock joint arthritis include excessive exercise, conformation resulting in asymmetrical loading, crushing of the small bones in the lower hock joints related to dysmaturity in neonates, septic arthritis (infection of the joint secondary to injury or injection), and fractures of the small bones in the lower hock region.

The majority of the time, the exact cause of lower hock arthritis is unknown but is likely related to a combination of factors. Diagnosis of lower hock joint arthritis begins with a lameness exam performed by your veterinarian, as mild lameness is typically the first clinical sign. Often back pain is noted as well, which is thought to be secondary to hock pain in these cases.

Due to the small size of these joints and their surrounding soft tissue, joint swelling is not typically seen with arthritis of the lower hock joints (unlike with OCD lesions and arthritis of the upper hock joint).

The horse may be sore in one or both hindlimbs, and will often become significantly more painful following flexion of the hock/stifle region. Blocking the lower hock joints can aid in making a more objective diagnosis (injecting the joints with local anesthetic and then watching the horse jog again to see if desensitizing this area resolves or improves the lameness).

Once the hock has been isolated as the source of pain, radiographs should be taken to assess the degree of boney change. Often severe bone remodeling and thinning of the joint space can be appreciated in the distal intertarsal and tarsometatarsal joints.

A multitude of treatment options are available for hock arthritis in the horse, ranging from conservative to more aggressive methods. For mild lameness, medical management of pain and inflammation with non-steroidal anti-inflammatory medications such as Bute, Banamine, or Equioxx to be used before and after ridden work may be sufficient. Oral (chondroitin sulfate, glucosamine, hyaluronan) and/or injectable (polysulfated polysaccharides such as Adequan or injectable hyaluronan) joint supplements may be of benefit as well. Shockwave therapy can be used for pain control and stimulation of blood flow and bone remodeling. For more severe cases, intra-articular therapy (joint injections) with corticosteroids (often paired with hyaluronan) should be considered. This treatment typically resolves or dramatically improves the lameness for weeks to months (varies depending on horse, severity of disease, frequency and intensity of work, etc.). With repeat injections, however, the duration of clinical improvement typically becomes shorter over time.

A multitude of treatment options are available for hock arthritis in the horse, ranging from conservative to more aggressive methods. For mild lameness, medical management of pain and inflammation with non-steroidal anti-inflammatory medications such as Bute, Banamine, or Equioxx to be used before and after ridden work may be sufficient. Oral (chondroitin sulfate, glucosamine, hyaluronan) and/or injectable (polysulfated polysaccharides such as Adequan or injectable hyaluronan) joint supplements may be of benefit as well. Shockwave therapy can be used for pain control and stimulation of blood flow and bone remodeling. For more severe cases, intra-articular therapy (joint injections) with corticosteroids (often paired with hyaluronan) should be considered. This treatment typically resolves or dramatically improves the lameness for weeks to months (varies depending on horse, severity of disease, frequency and intensity of work, etc.). With repeat injections, however, the duration of clinical improvement typically becomes shorter over time.

In particularly severe cases where joint injections are no longer effective or have an effect for only a short period of time, chemical or surgical fusion of these joints is the next step.

Because the lower hock joints are low motion joints, fusion or permanent stabilization of these joints is a viable means for eliminating the pain and inflammation associated with severe hock arthritis without compromising the horse’s way of going. Because the pain associated with arthritis is due to instability and bone on bone contact where healthy cartilage is absent, fusing the joint to eliminate the space altogether (the lower hock essentially becomes one block of solid bone) results in

resolution of pain.

Chemical fusion is performed by injecting the joints with either monoiodoacetate or ethyl alcohol with the intention of destroying any remaining cartilage to facilitate growth of new bone across the joint space.

Ethyl alcohol also blocks sensory innervation in the joint, providing analgesic effects. While less invasive than surgical fusion, chemical fusion is not without potential complications and should be performed in a controlled environment with radiographic guidance; often the procedure has to be performed more than once to result in fusion.

Surgical fusion of the distal intertarsal and tarsometatarsal joints can be performed via several different methods (laser application to destroy articular cartilage, drilling across the joint space, placement of bone plates or screws across the joint space).

Lower hock joint arthritis impacts performance in many horses, from mild attitude changes and a decreased willingness to work to severe lameness.

Many treatment options are available and when used individually or in combination typically provide a good prognosis for getting your equine athlete back to peak performance.

Megan Williams graduated from Kansas State University and went on to an internship at Ocala Equine Hospital. She completed her surgical residency at Michigan State University. Dr. Williams is a surgeon at Saginaw Valley Equine Clinic and a lameness diagnostician with GameTime Sports Medicine at major AQHA events around the country. You can email her at megan@saginawvalleyequine.com or visit her at www.saginawvalleyequine.com. You can also write to her in care of InStride Edition.

You must be logged in to post a comment Login