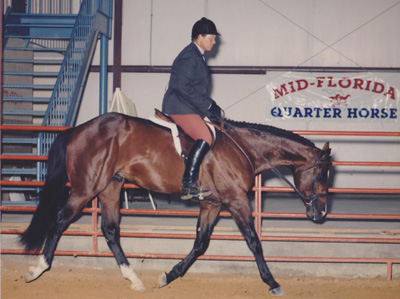

My Lucky Detail & Lauren Eichstadt

Winning Equitation Over Fences rides appear effortless. Horse and rider work in harmony to execute tight turns, negotiate stride lengths and float over each fence. Ask any over fences exhibitor and they will tell you, a good “go” is far from effortless. “A well designed course tests a rider’s ability to plan out the best route for their horse’s ability, the stride length and turn option,” says Lauren Eichstadt of Greenville, Pennsylvania.

Eichstadt, who has a long list of accomplishments, including a win in Amateur Equitation at the 2013 Quarter Horse Congress and a Reserve Championship in 2014, says “Equitation Over Fences is a true test of a rider’s skills.”

Contrary to what riders may think, an over fences course is not designed in and of itself to determine the outcome of the class.

“It should be a fair test that is challenging, but not too hard,” says Patrick Rodes, a “R” licensed United States Equestrian Federation (USEF) course designer who also designs courses for the American Quarter Horse Association (AQHA), United States Hunter Jumper Association (USHJA) and other events. “Riders should be able to separate themselves by the way they ride the course.”

Accuracy is imperative, but a flawless ride may not be the winning ride.

“I don’t necessarily kill a rider for a bobble, like a stumble. Instead I look for how the rider reacts and is able to turn a bad ride into a good ride,” says Jerry Erickson of Sanger, Texas, who holds judging cards from the AQHA and National Snaffle Bit Association (NSBA). “Sometimes I’ll even credit a rider for their ability to handle a situation.”

An Equitation Over Fences class is an opportunity to demonstrate one’s ability to make adjustments in a matter of seconds and work in concert with their horse. “It’s very technical it’s about deciding where and how tight to turn while being pretty and efficient,” says Kiersten Sapp, of Tallahassee, Florida.

Patrick Rodes

“A good equitation course asks questions that are customized to the level of competition and the best riders will rise to the top,” says Lainie DeBoer, an AQHA Professional Horseman with a specialized AQHA judging card who owns and trains at Dreamfield Stables in Forest Lake, Minnesota.

Many course designers say they feel it is their duty to the exhibitors as well as show management to construct courses that are meant to help riders show off their horse and score high for having a good round.

“The best way to start a course is to have a great first fence,” says Tucker Williams a USEF “R” licensed course designer who also owns Classy Courses, Inc. in Indiana.

Williams, who also designs courses for the ApHC National and World shows, APHA Youth and Open World shows, the Pinto World Show, the Pinto Color Breed Congress, AQHA events, USHJA and USEF events, designs his courses to encourage a rider’s confidence.

“As a designer, if I can locate the first fence in the arena to give the rider a long approach, this will maximize focus and set the pace for a successful round.”

well-chosen second fence builds upon a good first fence.

“It’s always a comfortable feeling to have the second fence as a single jump, especially if a green horse or novice rider is showing,” he adds.

He’s also careful to keep lines well out of the corners and providing plenty of approach is a necessity for riders of all levels.

“When the competitors walk their course and before the class starts I do not want them to feel like they are forced to take risks, but instead that they have options for different routes on course that match their level of confidence,” he explains.

Designing a course for the level of competition creates a positive experience for riders. Before deciding on jump placement, Rodes thinks about the level of rider that will be on course. “A schooling show and an A-rated show require varying degrees of difficulty,” Rodes emphasizes.

A standard equitation over fences course typically includes eight jumps.

“The distance between each jump is usually set on five strides, an average of 72 feet,” he says, “to make the course a bit harder, the line could be extended to 74 feet to ask a rider to ride more forward.”

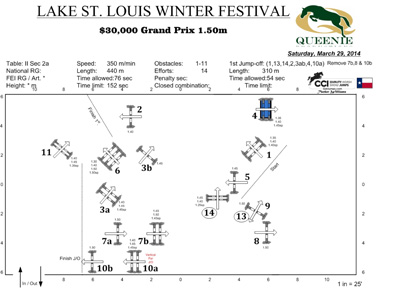

Once he determines the degree of difficulty for a course, he considers the size of the arena. “I use Visio (software), which puts everything to scale for me,” Rodes says, “that way I know if the course is going to fit.” The dimensions of the ring determine the number of strides and lines that can fit into a course.

Once he determines the degree of difficulty for a course, he considers the size of the arena. “I use Visio (software), which puts everything to scale for me,” Rodes says, “that way I know if the course is going to fit.” The dimensions of the ring determine the number of strides and lines that can fit into a course.

Over fences courses offer designers the flexibility of using one set of equipment to create multiple variations and degrees of difficulty in the same ring.

“There may be one course set in the ring, but I will build three tracks of courses off that course,” Rodes says.

Finally, he takes into account the location of the in-gate.

“I like to start on a single line with a jump coming home to get them flowing along,” Rodes says, “I also don’t put an in and out or combination too early in the course.”

At most shows judges are provided a course to judge, though they have the opportunity to request changes. “The actual course design doesn’t affect me a lot, but the actual fences and how they are lined up does,” Erickson says, “horses have poor depth perception and a fence with three or four rails straight up with a box increases the chance a horse will jump poorly or pull rails.”

Instead, he’d rather see a three or four rail fence with a large flower box in front of it and spruce boughs around the bottom of the standards to allow a horse to jump with more quality.

Sandy Vaughn

Stand out from the crowd

A bold, confident rider demands the judge’s attention. “On a line where riders have the option of riding a line in eight or nine strides, a rider who pushes their horse forward and hits the jump in eight will get bonus points from me,” Erickson says.

DeBoer agrees, she too rewards determined riders. “If there is a place to make a tighter turn or eliminate a stride in a bending line, I choose the more determined ride with the higher risk if it fits,” she says, “I don’t want to see anybody be reckless, it has to be smooth and well executed to gain my attention and earn points.”

Courses that incorporate bending lines offer judges a glimpse of a rider’s ability. “If the exhibitors can negotiate around a course and have the ability to lengthen and collect their horse, understand track work through a bend and have the ability to negotiate a correct balanced turn, they possess the capabilities of an effective rider,” DeBoer says.

Riders, trainers and judges agree courses designed for world class events are hitting the mark, providing enough of a challenge for riders to distinguish themselves from the rest of the class. However, courses set at weekend shows could be more challenging.

“The courses at weekend shows are too easy, making it difficult for amateur riders in the top to be separated out,” Eichstadt says.

A lack of equipment and resources make it difficult for weekend breed shows to offer the higher caliber over fences course like those found at world championship shows. Often smaller shows rely on borrowed equipment and volunteers to put a course together.

“The smaller weekend shows often don’t have the equipment or resources to do a quality course,” Erickson explains.

Looking to the hunter/jumper circuit could also increase the degree of difficulty in over fences courses. “I’d love to see a handy hunter round, like those at hunter shows, offered in the Quarter Horse world,” Eichstadt notes, “it would give more advanced horses an opportunity to show off their higher level of skills.”

Kiersten Sapp

Practice makes perfect

Do your homework. “If you go to the show unprepared, you could not only scare your horse, but possibly get hurt,” DeBoer says.

Schooling at home is about mastering the basics. “Your horse has to be comfortable with the height and look of fences you’ll be jumping at shows,” Eichstadt says. Set up a course at home and be sure you’re proficient over those jumps. “Once your horse is comfortable with the height and the look of the jumps work on one jump and your approach to the jump. Then add another jump.”

Practicing is more than soaring over fences, it’s about learning to manage a horse’s stride length. “At home I work on lengthening and shortening my horse’s stride so that if we get into a line too fast I can make an adjustment,” Sapp explains.

Seek the advice of more than one professional. “There are times I’ll take my clients to different trainers for a lesson. Even though we’re all saying the same things, they may use a different verbiage that a rider is able to understand better,” Erickson notes.

Take advantage of online resources. “Equestriancoach.com and usefnetwork.com are two amazing websites where you can gain a ton of knowledge,” DeBoer adds.

Show time

“Strategy is everything if you want to win,” Williams says, “make your plan of attack of how you will negotiate a course in the show pen and make notes of where you believe your weak points will be and adjust your plan accordingly.”

Memorizing an equitation over fences course is trickier than a working hunter course. “Personally I memorize the order of fences based on a feature or color,” Sapp says, “I’ll plan my route and think roll-back to red fence or the tan fence or remember the color of the flowers.”

Some courses set two jumps side-by-side. “I’ve managed to go off course a time or two forgetting a jump or jumping the same one twice,” Eichstadt adds.

To reduce her chances of going off course, Eichstadt uses her cell phone to take a picture of the course she’ll be riding. Then she’ll stand in the bleachers outside the ring where the course is set and look at set course at the same time she looks at the diagram. “I walk the course if I have a chance to see how the jumps line up in the arena,” she adds.

Study your courses and if you don’t go early in a class watch other riders to see what works for other riders in the ring. “Know your horse and his stride length,” Rodes advises, “does he have a lot of stride or can he compact to slow and steady strides.”

Above all else, a confident rider will rise to the top of the class. “A confident rider that negotiates the course with a clear relationship with their horse will automatically set themselves apart from the other competitors,” DeBoer concludes.

You must be logged in to post a comment Login