With the ever-increasing advancements in equine sports medicine, injecting joints has become a kind of normalcy across the disciplines in the equine world.

While injecting joints has many positive effects in maintaining your show horse, complications can occur. Therefore, it is critical to be educated on how to reduce the likelihood of a joint infection.

Here, veterinarians provide insight into their standard lameness examinations, the necessity of joint injections, what joints in particular most commonly need routine care, the importance of after care and how to recognize an infected joint.

Also, trainers and owners who have had negative experiences with joint injections share their perspective on what they feel fellow horsemen should know before they give the go ahead to inject.

———–

Dr. James Hassinger, DVM of Aberdeen, North Carolina is a graduate of North Carolina State University and Auburn University School of Veterinary Medicine. He has been actively practicing veterinary medicine for 31 years. In 2003 Dr. Hassinger narrowed his focus and opened Hassinger Equine Service in Aberdeen as a sports medicine and performance centered practice dedicated to equine lameness, performance management, rehabilitation and imaging. Dr. Hassinger is also an active rider at Hassinger Farm and shows along the East Coast.

Dr. James Hassinger, DVM of Aberdeen, North Carolina is a graduate of North Carolina State University and Auburn University School of Veterinary Medicine. He has been actively practicing veterinary medicine for 31 years. In 2003 Dr. Hassinger narrowed his focus and opened Hassinger Equine Service in Aberdeen as a sports medicine and performance centered practice dedicated to equine lameness, performance management, rehabilitation and imaging. Dr. Hassinger is also an active rider at Hassinger Farm and shows along the East Coast.

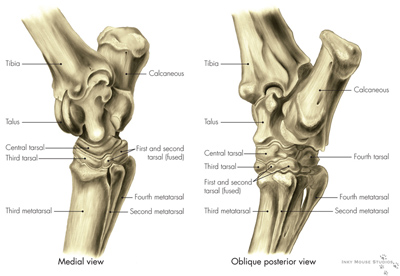

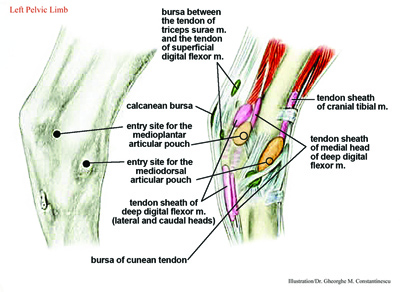

Dr. Hassinger typically injects an average of 250 joints a month. At certain times during the year, before a big event like the Quarter Horse Congress, he will see an influx of customers typically about a month before their horse is scheduled to show for routine maintenance so that their horse is at the top of its game for the event. The most common joints Dr. Hassinger injects are hocks which include the tarsomentatarsal and distal intertarsal joints. In Western Pleasure horses, he most commonly sees issues with hocks and stifles.

“The first benefit that the joint receives from a routine injection is that it is an immediate anti-inflammatory. This is achieved by the corticosteroid that is added to the injection,” Hassinger says.

“The hyaluronic acid that is included in a routine injection does two things. First, it is an anti-inflammatory whose effects are seen two to seven days after the injection. Second, it restores viscosity to the synovial fluid adding lubrication and cushion to the joint. These two drugs and three benefits work together to reestablish a normal healthy environment within the joint. Once the joint is returned to a healthy state it will slow down degenerative joint disease or arthritis.”

Although joint injections do help prevent damage, Dr. Hassinger does stress that they are not a cure-all method.

“Routine injections every six to 12 months is normal and if they are not achieving the desired effect or length of time, we move to other treatments such as IRAP (Interleukin-1 Receptor Antagonist Protein),” he says.

When a new horse arrives, Dr. Hassinger has a typical standard lameness exam he follows to establish where the horse has a problem and how best to treat it.

“First a thorough history is taken from the owner and or trainer,” he says. “Then, each leg is palpated weight bearing and non-weight bearing. During this time, it is noted if there are any joints that are effusive and any ligaments that are enlarged or painful. Next, the cervical spine is then flexed both ways and the thoracic spine is palpated and any areas of pain or resistance are noted. Lastly, gentle pressure is applied to the lumbar muscles, muscles over the sacroiliac ligaments and the whorl bones (trochanteric bursa) to detect any sore areas.”

Dr. Hassinger then examines the horse in motion and usually has the horse jogged going away or coming toward him on both a soft and hard surface. He also likes to see a horse jogged in a circle both directions on both a soft and hard surface. Depending on the circumstance, he then sometimes has the horse longed or ridden as well.

Dr. Hassinger then examines the horse in motion and usually has the horse jogged going away or coming toward him on both a soft and hard surface. He also likes to see a horse jogged in a circle both directions on both a soft and hard surface. Depending on the circumstance, he then sometimes has the horse longed or ridden as well.

” Then, a flexing exam takes place where each leg is flexed twice, a distal flexing exam and a proximal flexion. After the flexing exam is completed, I now have all the information I need on what treatments or further diagnostics need to be pursued,” he says. ” The next step could be routine injections, a blocking exam, radiographs, an ultrasound exam, MRI (magnetic resonance imaging) or nuclear scintigraphy (bone scan).”

Dr. Hassinger explains that he works on a case-by- case basis as far as taking radiographs before injecting because X-rays are not needed in every circumstance and depends on so many different factors like if it is routine maintenance on the horse, how lame the horse is and if it is an acute or chronic lameness.

“Every case is different and the history and severity of the lameness is used to determine the necessity of radiographs,” he says.

After the lameness exam, if Dr. Hassinger feels the horse does need routine joint injections, he typically follows a standard procedure.

“The horse is taken to a treatment room and the joints are prepared by scrubbing with Chloroxadine 4 percent scrub for five minutes or until they are clean and letting the last scrub soak for seven minutes to ensure the injection sites are sterile. If the joint to be injected is on a pelvic limb the tail is tied up prior to scrubbing,” he says. “The horse may be sedated before scrubbing or right before injections occur depending on the demeanor of the particular patient. At the end of the seven minutes, the injection sites are wiped off with alcohol, a twitch is placed on the horse and then the joint injections occur. The horse is administered an NSAID (non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug) intravenously then the remaining scrub is rinsed with water. The horse returns to a stall to wake up and then is trailered home. I recommend to clients that the horse is to have 24 hours of stall rest and two days off work. No additional medications are needed to be given at home.”

Over his many years as a veterinarian, Dr. Hassinger has found joint injections to be a safe, effective method in helping show horses perform at their optimum.

Over his many years as a veterinarian, Dr. Hassinger has found joint injections to be a safe, effective method in helping show horses perform at their optimum.

“My practice has a very good record of little to no adverse reactions to joint injections,” he says. ” If one takes the time to properly prepare and uses quality medications there is little risk associated with joint injections.”

Dr. Hassinger does also recommend joint supplements as another method of maintenance care.

“I recommend polysulfates like Adequan or Pentosan. My personal horses are on Pentosan. I administer the loading dose which is 6cc IM (intramuscular) every seven days for four injections and then the maintenance dose 6cc IM every two weeks,” he says.

Dr. David Stephens, DVM, DABVP of Aubrey, Texas graduated from Texas A&M University in 1990, completed his surgery residency at Oklahoma State University in 1994 and became a Diplomate of the American Board of Veterinary Practitioners (Equine) in 1995. In 1997, he partnered with Dr. Scott Weems to establish Weems and Stephens Equine Hospital where he still practices from today.

Through the years, Dr. Stephens seldom sees instances of complications from joint injections. Although, he does stress that he has strict protocol on preparing for injections and always exercises great care and precaution when injecting a joint.

“Dilution is the solution to pollution,” Stephens says. ” In my opinion, you must practice good surgical procedures and sterile techniques. About 75 percent of the joint injections I do are treated here at the hospital where we are able to control the area where the horses are treated.”

Dr. Stephens would prefer conducting joint injections in an environment like his hospital where he can work on concrete floors and control the cleanliness of the area. However, situations do arise from time to time where he does have to work in less than ideal conditions whether it be at a horse show, training track, or farm.

“If your horse has known joint issues, I advise getting your horse worked on prior to the event you are competing in because you can get the work done in a calm, controlled environment which does greatly reduce the likelihood of getting a joint infected,” he says.

Dr. Stephens believes in conducting two scrubs prior to injecting. He does a five minute “rough scrub” where he uses a surgical brush, soap, and hose to get all ” the garbage of the skin.” Then, he does a “surgical prep scrub” where he uses gloves in an aseptic fashion and cleanses the entire area for 10 to 12 minutes. He also wipes alcohol on and off the area several times following the scrub before injections are administered.

Dr. Stephens believes in conducting two scrubs prior to injecting. He does a five minute “rough scrub” where he uses a surgical brush, soap, and hose to get all ” the garbage of the skin.” Then, he does a “surgical prep scrub” where he uses gloves in an aseptic fashion and cleanses the entire area for 10 to 12 minutes. He also wipes alcohol on and off the area several times following the scrub before injections are administered.

“After care is very important. We usually put a sterile bandage on the site of the injection and ask the client to leave the bandage on for three to four hours afterward,” he says. ” Ideally, I would like for the horse to have off for 48 to 72 hours. I suggest the first day off on stall rest, the second day at light exercise and usually by the third day the horse can go back to regular work routine. The injections do have a better effect and get their maximum response a few days after the injection is performed.”

If a client does have a problem at an event and is forced to deal with options to get their horse to perform, Dr. Stephens recommends to keep good, open communication between the veterinarian, owner and trainer. He stresses the importance of weighing out all the options both positive and negative and really being realistic as to whether the horse will be ready to compete while always keeping the best welfare of the animal first and foremost.

If a horse does establish an infection, Dr. Stephens explains that the type of bacteria and timing of when he first gets to treat the horse are key components in the success or failure of saving the horse. For instance, an up-and-coming bacteria, MRSA (Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus Aureus) is a type of “super bug” or hard to treat staph infection that is antibiotic resistant and very difficult to overcome. It is also hard to pin point exactly where the bacteria derives from. Although Dr. Stephens explains that in the past, MRSA has mostly been a bacteria that has been a problem among humans at hospitals where health care aids are regularly tested as carriers, it is starting to be seen more than before in horses.

“If you notice anything unusual around the joint or with the horse in general, it is really important to consult your veterinarian immediately,” he says. “The proximity and availability of your vet at the time may determine what the client should do with the horse. It just totally depends on the situation but calling your vet at the first sign of an issue is crucial.”

Top American Paint Horse Association trainer, Tim Gillespie, of Gainesville, Texas and wife Shannon, of Gillespie Show Horses, lost one of the very best horses they have ever had to a joint injection complication. Four-time APHA World Champion, A Good Intention’s joint became infected with MRSA.

Top American Paint Horse Association trainer, Tim Gillespie, of Gainesville, Texas and wife Shannon, of Gillespie Show Horses, lost one of the very best horses they have ever had to a joint injection complication. Four-time APHA World Champion, A Good Intention’s joint became infected with MRSA.

“Our world is so busy these days and the vets are expected to work faster and faster,” Gillespie says. “There are assembly lines for the vets at shows and everyone is in a hurry. I just think we should try to be educated about joint injections and the higher risk of infections at big events because of the fast-paced atmosphere.”

As Gillespie explains, there are two kinds of vets. There are show horse vets and home vets. With the added pressure of big events, show vets are under added strain to help clients get horses sound immediately so they can show.

“As I understand a lot stronger steroids are injected at horse shows to try get the horse a quick fix and I do not think people know or ask what the vets are injecting and what side effects the increase in steroids can have,” he says. “We need to study this stuff and be aware of what the vets are injecting and also really watch the techs and make sure they are wearing gloves at all times and are scrubbing these horses thoroughly enough before injecting.”

Gillespie is a firm believer in joint injections and is still and an advocate of having his horses injected for regular maintenance. He has, however, become much more aware of excessive use of steroids at shows.

“You are much better off having your vet at home, who you know and trust, go over your horses thoroughly when they have ample time to examine,” he says. “You should also give your horses some days off at home before going to a show.”

Gillespie also feels it is imperative for fellow horseman to be educated on what an infected joint looks like so they know what signs to look for right from the start. He also stresses that it is crucial that you have your horse examined immediately by a professional if you see an inflamed joint because sometimes if the infection is caught early on it can be calmed down and the horse can be successfully treated.

Janet Fortenberry, of Farmerville, Louisiana, owner of A Good Intention, explains how absolutely devastating the loss of their horse last year has been for their family and especially for daughter, Anne Marie, who grew up with him.

“I just think people need to be really, really cautious before they decide to do injections,” Fortenberry says. “We learned the biggest lesson of our lives. It was very costly and really, really hard on my family to get over. We have just been devastated.”

Even though top Western Pleasure trainer, Ashley Lakins of Wilmington, Ohio has had a bad experience with a horse that she and husband, Kenny trained that resulted in a steroid founder, she does still believe in injecting joints. However, she now has educated herself more on the subject and encourages fellow horsemen to do the same.

“Be as educated as you can be about injecting joints,” Lakins says. “Be aware that complications can arise and be cautious before you make the move to inject right away, especially at a show.”

Although Lakins is aware of the added pressure that big futurity payouts put on trainers to get horses ready for a certain event, she encourages her clients to put the welfare of the horse first.

“I advise to try the best you can to not inject your horse at shows. If your horse is not sound before you take it and your regular veterinarian can not get the problem resolved do not think you can make it sound when you get there,” she says. “Horse show vets are often more rushed and they do not know your horse’s history like your regular veterinarian would. To me, injecting joints is not useful at a horse show anyway because there usually is not enough time to give the horse the right amount of time off.”

Lakins also stresses having a good relationship with your vet at home and advises calling your regular veterinarian to discuss options if you do run into problems at a show. When doing joint injections, Lakins also feels it is crucial to take into account other added stresses like hot weather, hauling, the show environment and extra riding.

“I really encourage getting a second opinion before you rush into doing work at a show especially with a horse show vet who only knows what you are telling him about your horse,” she says. “I also think it is a good idea to have your regular vet talk to the horse show vet before work is done so they can go over your horse’s history and exactly what previous work has been done.”

Also, Lakins really feels the horse’s overall conformation and willingness to be trained are both huge role players in the overall soundness and likelihood of needing joint injections down the road.

“We try to get our horses used to being ridden a little fresh so we don’t need to longe so much. We have found it helps horses stay sounder longer,” she says. “Horses with ‘form to function’ conformation tend to have less stress on their joints than horses that are poorly conformed, like for instance a horse with really crooked front legs. Also, a horse that has a big motor and needs a lot of longing and excessive riding to perform well will be more likely to have soundness issues.”

3 Responses to "What to know before you inject"

You must be logged in to post a comment Login