Terri Layer gives Barry Malphrus a lesson.

We often take for granted the ease with which we step into the stirrup, throw our leg over the saddle and head into the practice pen or show arena. When the process of mounting and riding is second nature, it’s easy to lose sight of the big picture, how lucky we are to have the freedom to saddle, ride and compete unrestrained by physical challenges or medical conditions.

Imagine that an accident, an ailment or a physical challenge changes that.

Instead of prepping and showing on your own, your trainer, family and friends have to assist with the most basic tasks and just getting on is an accomplishment.

Now imagine that despite physical limitations, you’re competing at regional and world championship shows and the All American Quarter Horse Congress.

It takes an extraordinary trainer/client/horse partnership to make this happen.

No one knows this better than Jon Barry and Dana Smith, Terri Layer and Barry Malphrus, Kim Myers and Stacey Minoglio and Bruce Walquist and clients, Nancy Kogucz and Fred Johnson.

We’ve asked these riders and trainers what it takes to be successful and they’ve graciously shared their stories.

Two and a half decades ago, American Quarter Horse Association (AQHA) Professional Horseman Jon Barry and amateur rider Dana Smith, were pioneers. Smith was the first rider with physical disabilities to compete in Amateur Western Pleasure events on a national level. An accident at 23-years-old left Smith paralyzed from the chest down

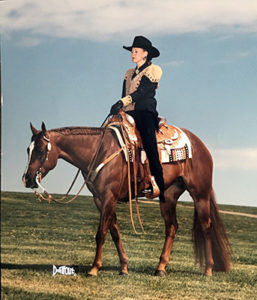

Dana Smith riding Shesa Hot Cookie.

“When she came to me, she told me she wanted to do everything she did before the accident,” Barry said, “she had an unbelievable dedication to showing.”

During their partnership, Smith qualified for the AQHA World Championship Show six times with multiple horses.

“A lot of people think I am a paraplegic, but that’s not the case,” she said, “I had a neck injury and have no muscle control from the neck down.”

Bruce Walquist of Walquist Quarter Horses in Cleburne, Texas coaches amateur riders, Nancy Kogucz of Texas and Fred Johnson of California. Kogucz, has shown at AQHA events since the 1980s and currently competes in Western Pleasure with She Looks Expensive, a 2009 brown mare by Blazing Hot and out of Elegant Invitation. An injury and a combination of medical conditions impact her balance, physical and motor movement and her bones fracture easily.

“A lot of people stop pursuing their goals because they think they can’t do something,” Kogucz said. “Every time I get up on my horse I take a risk and to accomplish that goal is a boost in self-confidence and encourages me to consider what else I can do.”

Fred Johnson and Mac In Time.

Raised on a ranch in Colorado, Johnson regularly competed in Western Pleasure, Reining, Horsemanship and Halter classes at Northeast Colorado Quarter Horse Shows. In 1993, an accident left Johnson blind in his right eye. Two years later retinal glaucoma claimed the sight in his left eye.

With Walquist’s coaching, Johnson showed Mac In Time, a 2001 palomino gelding by Macs Good N Plenty and out of Bar Lady Time to PHBA World Championship titles in both 2005 and 2006. In the show pen, Johnson wore a headset so that Walquist could tell him when he was riding into or out of a corner or when he needed to pass.

“Getting back to riding after losing my sight changed my whole life and brought me back to my senses,” he said, “and Bruce is a talented horseman who helped achieve my goal of winning a world championship.”

In Georgia, Terri Layer of CrossRidge Ranch trains Barry Malphrus, helping him prepare for amateur western pleasure events. This fall, Malphrus, who was born with cerebral palsy, is showing Preferred Potential (Freed), a 2001 brown gelding by Potential Investment and out of Eager Leaguer, at the Quarter Horse Congress.

“When we first bought Freed the horse’s barn name was Fred,” she said. “Barry didn’t really like that name, but he didn’t believe in changing a horse’s barn name. So, we added an “e” to make it Freed, which is what he feels when he rides.”

Stacy Minoglio riding Sleepin Around.

In the northeast, Kim Myers, an AQHA judge and trainer from Felton, and his wife Renee, Pennsylvania works with Stacey Minoglio. Aboard Sleepin Around, a 2007 sorrel gelding by Too Sleepy To Zip and out of Dox Sweet Version.

Minoglio competes in Ranch Pleasure. As a youth exhibitor, Minoglio showed in Horsemanship, Reining and Hunter Under Saddle events.

Driving home one evening, she was the victim of a hit and run accident. Her injuries were severe.

“When I woke up out of a coma, they told me my injury was the equivalent of someone having four strokes,” she said. “They also told me I’d never walk again. I told them that I didn’t want to walk, I wanted to ride.”

Finding the Right Horse

Even though Sleepin Around, the horse Myers sold to Minoglio to show was only a 3-year-old at the time, he had the right mind set and seemed to “sense” what his job was.

“Horses, like people, have personalities and will work better with some people than others and making the right match is important,” Myers said.

Barry adds, that working with Smith taught him a lot about horses and their “fit” for a rider.

The first horse Smith rode was cranky, almost ring sour. The mare would feel a rider’s legs tense against her sides, drift off the rail and react. But with Smith, the mare improved in her performance.

“What I learned was that it was actually the people that make horses nervous, not vice versa,” Barry said. “Because Dana’s legs couldn’t get tense, she didn’t get nervous and the mare stayed relaxed.”

Temperament, mind set and trainability are all part of the equation.

“I look for that horse that is kind and steady,” Layer said. “I want a horse with a big heart. Those horses tend to have big soft eyes that allow you to look into their soul.”

“When you find the right horse, it will respond to your abilities,” Malphrus said.

Natural movement is an equally important consideration.

“The horse has to have a natural, not manufactured, ability for the event they will be showing in,” said Barry. “For riders who don’t have the use of their legs, the horse has to have natural self-carriage.”

Smith agrees.

“I couldn’t ride a rough gaited horse because I couldn’t put weight in my stirrups to absorb some of the impact and it wouldn’t create the picture we were going for in Western Pleasure.”

Walquist has had the same experience.

Nancy Kogucz and She Looks Expensive.

“The horses have to be natural and good with their cadence and rhythm and have a lot of self-carriage,” he said. “Nancy’s mare is a very good loper and doesn’t require as much leg as other horses.”

In addition to all of the qualities mentioned above, the horse’s talents have to be a good match for the rider’s goals and abilities.

“Everyone told me I should get an old warhorse to safely pack me around,” Johnson said, “I prefer young ones that aren’t burned out on showing and have the ability to be taught.”

Part of finding the “right” horse includes finding a horse that is willing to accept nontraditional cues. Riders who don’t have the use of their legs rely on verbal cues and the reins to guide their horse.

For example, Layer has trained Preferred Potential to execute a lope departure when Malphrus positions the reins slightly toward the fence and uses a verbal cue.

“Moving the rein slightly toward the fence is similar to putting a leg on the horse and he knows which lead to come off on,” Layer said.

Johnson, on the other hand, needs to use more leg.

“I have to use my inside leg to hold a bit more than most horses and sometimes that takes a bit of getting used to for the horse,” he explained.

Barry and Smith found a training routine that kept the horses in peak condition while allowing Smith optimal riding time.

“Jon would ride my horse for a few weeks, then send the horse home for a couple weeks so I could ride and then we’d go back to him so he could see what we were having trouble with,” Smith said.

Finding Balance

There is a delicate balance that trainers and riders with physical challenges have to find. Support and encouragement must be a given, but so too, must be honesty and realistic goal setting. Communication is that tool that brings trainers and riders together in their expectations.

“You have to find out how far that individual rider wants to go,” said Barry, “some may be OK with riding around the house. Others may want to be a top contender in the show pen. You have to talk with them to learn their goals and find out if they have the drive to make their goals happen.”

Fred Johnson with Bruce Walquist.

Trust is critical. In the show pen, Walquist serves as Johnson’s eyes. Walquist communicates to Johnson through a headset and lets him know when it’s time to pass or when another horse is cutting in front of him on the rail. Without a doubt, the two have a deeply rooted trust in one another.

“The tone he uses and the way he talks to me is a big part of that,” Johnson said, “even if he sees a wreck coming, he stays calm and collected so that I don’t get nervous.”

That’s important to Kogucz as well.

“Bruce is always three or four steps ahead of me in order to prevent a dangerous situation,” she said. “This builds confidence and trust that is required between me and my horse.”

Letting go is imperative. Layer is never far from Malphrus’ side in the practice pen at home and always has a feeling for where he is in the arena.

“I’ve always been super, super safety conscious with all my clients,” Layer said. “With Barry I am careful where I put him into the arena for a class and encourage him to do his best.”

Although she’s focused on safety, Layer knows when to take a step back and allow him to just ride. That in part, is what makes their partnership so successful.

“I understand that safety is paramount, but trainers have to be willing to push the rider to their fullest potential,” Malphrus insisted. “Too many people don’t want to push handicapped people because they think it’s mean. The trainer has to believe in you more than you do, to push you to your potential.”

Johnson could not agree more.

“The trainer has to have the guts to take you on,” he said. “Some will be too afraid that you’ll get hurt for the partnership to work out.”

On top of all the other characteristics, a trainer has to have empathy .

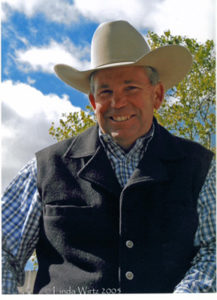

Jon Barry

“Jon is a compassionate, caring person and it made him happy to be a part of helping me achieve my goal, even when it meant extra effort and work on his part at the same rate his other clients paid,” Smith said.

Supporting a client during emotional ups and downs can be an element trainers aren’t accustomed to dealing with.

“After a catastrophic injury the rider may have good days where they are on top of the world and difficult days where they are screaming or yelling because they’re frustrated their body can’t do what it once did,” Myers said.

Finding the Right Event

Trainers encourage clients to choose specific events based on their goals and skills, but sometimes physical disabilities determine the event of choice. Myers knew he needed to find a suitable alternative for Minoglio who was previously successful in Horsemanship and Reining. Balance issues made it difficult for her to ride in either of those events and the loss of her peripheral vision made it difficult to ride in Western Pleasure.

“I judged a show in the Midwest and saw the newly added Ranch Pleasure class,” he said, “I immediately knew this was a good fit for Stacey.”

The intricate nature of the pattern corresponded to the aspects of Horsemanship and Reining that she loved as a youth. It is performed individually and if she needs to hold to the horse for balance, she can.

“I like competing in the performance classes so this was a perfect fit for me,” Minoglio said.

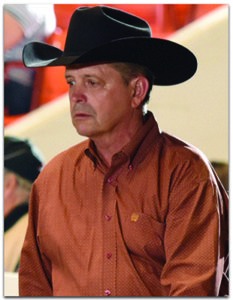

Kim Myers

The event has been a good match, she and Sleepin Around won the class at the 2016 Merial AQHA Regional Championship in New Jersey.

Kogucz agrees that the event has to be a good fit. She currently competes in Western Pleasure, but has hopes of competing in Trail and Western Riding.

“It all depends on how far and how fast this disease progresses,” she said.

Let’s Go Show

These four trainers agree that there’s not a lot they do differently for their clients as compared with other clients. In part, that’s their answer because their riders make it clear they don’t want to be treated differently.

“When I first met Barry, he told me he wanted to be treated like every other client,” Layer said.

For the most part, he is. He requires a special saddle that allows his feet to sit more forward toward the horse’s shoulders than a traditional saddle. And the custom made McLelland’s show saddle he competes in has a seat belt to secure him in the seat.

But ask the riders and they’ll tell you their trainers do go the extra mile to get them ready to show.

“Even the smallest things, like bringing my saddle to the barn with the golf cart, saves me an hour of time,” Minoglio said.

That includes pre-ring warm-up routines may need fine tuning or adjusting.

“I make sure I ride Nancy’s mare a little longer so she’s more tired going into a class,” Walquist explained.

Some riders take for granted that a trainer can jump on and tune the horse up in between cuts of large classes at the Congress or Worlds Shows.

“I was at a huge disadvantage,” Smith said, “because of the process it took to get me on the horse, I couldn’t get off in between go’s and have Jon tune up my horses.”

That meant extra practice at home, extra warm-up at the show and ultimately a good horse that knew its job.

Additional pre-planning may be needed when riders with physical challenges travel to shows. Depending on the rider’s situation, the trainer may need to help them apply for exceptions or answer questions at a show.

“We travel with a printed, signed copy of the AQHA rule that states adult riders are allowed to be seat belted in,” Layer said, “we’ll be taking it with us to the All-American Quarter Horse Congress just in case the inspector has a question.”

When Johnson wanted to return to showing, Walquist worked on his behalf to receive permission from AQHA and PHBA for Johnson to ride with a head set solely for the purpose of providing directional guidance, not coaching.

“I had to be real careful in my word choice in telling him where he was in the arena,” Walquist said, “I couldn’t tell him to go straight because that didn’t mean much to him.”

Conclusion

Accepting riders with physical difficulties into a training program can be an inspiring and rewarding experience for everyone involved.

“Horses may be the one thing that keeps people with a catastrophic injury going,” Smith said. “If you can be a part of helping them achieve their goals, it can be life changing.”

“Since starting to ride with Kim five years ago, my self-esteem has shot through the roof,” Minoglio said.

Myers pushes her to reach her fullest potential, but is always waiting outside the gate with a high-five when she is her own harshest critic.

“When I’m at the barn, I get treated like everyone else and that’s a big piece of why I like working with Terri,” Malphrus said.

You must be logged in to post a comment Login