Heel pain related forelimb lameness has traditionally been and continues to be one of the most common causes of lameness in Quarter Horses.

Heel pain related forelimb lameness has traditionally been and continues to be one of the most common causes of lameness in Quarter Horses.

While traditionally attributed to navicular disease, the introduction of advanced imaging techniques to equine practice demonstrates that a variety of soft tissue injuries in the foot can be responsible for heel pain, particularly when radiographs of the navicular bone are normal.

Diagnosis of heel pain in the horse begins with a lameness exam; the horse’s gait is typically evaluated in a straight line and in a circle traveling both directions. Often the lameness is accentuated with the affected limb on the inside of the circle. After the lame leg is identified, local anesthetic is used to temporarily ‘block’ or numb the heel and sole region of the foot, and then the horse is again observed for lameness.

When the lameness has been improved or abolished on the primarily affected leg, many will become sore on the opposite forelimb, indicating bilateral lameness with one leg more painful than the other; a second ‘block’ of that heel/sole region often results in near complete soundness in the front end. Next, radiographs should be taken of the foot or feet including views to highlight the navicular bone(s).

When substantial change is evident in the navicular bone, this may be sufficient to diagnose degeneration of the navicular bone or navicular disease. If the navicular bone and other boney structures of the foot/pastern region are relatively normal, suspicion of soft tissue injury within the foot is increased. Often the first logical step before pursuing advanced imaging is to exhaust any appropriate conservative treatments.

When substantial change is evident in the navicular bone, this may be sufficient to diagnose degeneration of the navicular bone or navicular disease. If the navicular bone and other boney structures of the foot/pastern region are relatively normal, suspicion of soft tissue injury within the foot is increased. Often the first logical step before pursuing advanced imaging is to exhaust any appropriate conservative treatments.

Foot radiographs are often useful to determine if any shoeing changes may be beneficial to change or improve balance; oftentimes subtle shoeing changes, with or without addition of pain and anti-inflammatory medications, may make a significant difference. If conservative management techniques do not result in significant improvement, the next step when possible should be advanced imaging, such as an MRI of the foot or feet.

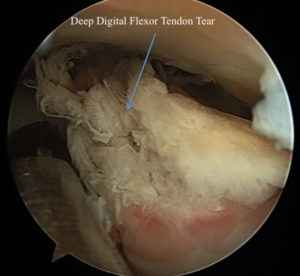

A multitude of soft tissue injuries have been diagnosed with MRI of the foot in horses with lameness isolated to the heel region. Potential diagnoses include: tears of the deep digital flexor tendon from the pastern region distally into the foot, adhesions (scar tissue which sticks or adheres one segment of soft tissue to another) between the deep digital flexor tendon and the navicular region, tears of the collateral ligaments of the coffin joint, inflammation or thickening of the collateral sesamoidean ligament (also known as the navicular suspensory ligament), inflammation or tears of the distal sesamoidean ligaments, edema/fluid within the navicular bone, distal border boney fragments off the navicular bone which may be difficult to see or diagnose with traditional radiographs, and others. Because ultrasound of the soft tissue structures within the hoof capsule is typically unrewarding, the addition of MRI as a diagnostic modality for the equine foot has allowed for much more specific diagnoses, and as a result more focused and potentially more effective treatment plans.

Many of the soft tissue lesions diagnosed by MRI of the equine foot are treatable primarily with rest and rehabilitation; other treatments based on the specific injury that may be employed could include platelet rich plasma (PRP) or stem cell treatment for soft tissue tears, joint, bursa, or tendon sheath injection with corticosteroid and hyaluronic acid to treat pain and inflammation, shoeing changes/therapeutic farriery, and bisphosphonate medications such as Tildren or Osphos.

Many of the soft tissue lesions diagnosed by MRI of the equine foot are treatable primarily with rest and rehabilitation; other treatments based on the specific injury that may be employed could include platelet rich plasma (PRP) or stem cell treatment for soft tissue tears, joint, bursa, or tendon sheath injection with corticosteroid and hyaluronic acid to treat pain and inflammation, shoeing changes/therapeutic farriery, and bisphosphonate medications such as Tildren or Osphos.

Injury to the deep digital flexor tendon within the tendon sheath or navicular bursa, with or without adhesions, is one of the more commonly diagnosed lesions on MRI of the front feet, and surgical debridement of these lesions and removal of adhesions is often beneficial.

A 2012 Equine Veterinary Journal article by Smith and Wright evaluating horses that had endoscopic surgery for evaluation and treatment of the navicular bursa found that 63 percent of cases were sound and in work following surgery.

In some cases, horses will be chronically sore in the front feet, with little to no change from conservative therapies, and have a relatively normal MRI.

For these cases the advanced imaging may still be of some benefit, as it indicates that the horse is a structurally sound candidate for palmar digital neurectomy (surgical transection and removal of a portion of the nerves that supply sensation to the front feet). Ruling out major soft tissue injuries within the hoof capsule and substantial degenerative change of the navicular bone itself serves as reassurance that some of the risks associated with surgical neurectomy are relatively low (tendon rupture, coffin joint luxation, and navicular bone fracture are potentially life-ending complications that can be associated with palmar digital neurectomy).

Advanced imaging techniques have taught us that diagnosis and treatment of lameness isolated to the front feet can be much more complex than we once realized. While the approach to diagnosis and treatment has become more complex, we have also gained a great deal in our options and abilities for treating these cases, and for getting these horses back to peak performance.

You must be logged in to post a comment Login