Rebecca Bailey’s American Quarter Horse Association (AQHA) mare Ona Impulse was a Western Pleasure powerhouse in her day. She won the Open 2-year-old Championship at the Congress and the AQHA World Championship Show. As a 3-year-old, won the Open 3-Year-Old Western Pleasure at the Congress and has an AQHA Youth World Championship to her credit. A mare of that caliber is destined for breeding, whether she carries her own baby or a recipient mare does the work.

Bailey, who owns AQHA World and Congress Champion One Hot Krymsun was eager to produce a foal from this cross.

At first the Ohio native had no problems flushing embryos. The mare actually built too many follicles each cycle, which eventually started to interfere with the flushing process.

“The vet would tell us there were so many we should wait and start her all over again,” she said.

As the mare aged, her uterus had reoccurring infections, making artificial insemination or embryo flushing difficult.

In 2014 Bailey was facing the end of the breeding season with no luck at recovering an embryo from Ona Impulse. It was then that her veterinarian suggested she try Intracytoplasmic sperm injection.

In this process, oocytes, or eggs, are recovered from the mare’s ovaries using ultrasound guided transvaginal follicular aspiration. A laser is then used to drill a hole through the outer layer of the egg and a single sperm from a stallion is then gently injected. After the ICSI procedure, the newly fertilized egg is cultured in a laboratory incubator for about eight days, so the embryos will develop. Successful embryos are then transferred into to a surrogate mare. Although intracytoplasmic sperm injection had been tested in rabbits, cattle and humans, the process had not been attempted in horses until 1996 when the very first ICSI foal arrived. Fire Cracker was the result of work at Colorado State University.

As a last resort, Bailey did go ahead with the procedure and although eggs were successfully recovered, none resulted in a successful pregnancy.

“I was reluctant to try again at that time because I assumed the process would become too expensive,” Bailey said. “I later found out that in many cases, the actual cost of using ICSI process can wind up being comparable or even less than in a traditional embryo transfer.”

Bailey spent the next two years trying to clean up infections in Ona Impulse and ended up with no pregnancies. Then, in 2017 Bailey decided to try ICSI again.

“I waited until I knew Ona had built up a lot of follicles and I took her to the clinic and told them I needed them to get as many oocytes as possible,” she said. “They got 14.”

Bailey ended up with two successful fertilized eggs that year – one by One Hot Krymsun and another by Red White N Good, another stallion she owned at the time. She also sold one oocyte to Jerry and Dr. Laura Bracken, who successfully produced an embryo by their stallion Sophistication Only. She was also able to successfully freeze two additional oocytes for potential future use.

While ICSI was first developed for use primarily in older or difficult to breed mares, breeders have turned to the in-vitro technology for other reasons. In 2013, Jason Martin and Charlie Cole, of Highpoint Performance Horses in Pilot Point, Texas, first tried the method with several of their high performing rodeo mares.

“If they had to be on the road, then we could still try to get a baby by doing ICSI instead of having the downtime of having to bring the mare back to get flushed,” said Christi Christensen, Highpoint’s breeding manager.

When Bremen, Indiana AQHA breeders and exhibitors Richard and Betty Carr purchased I Will Be A Good RV, the sales contract included provisions for the sellers to retain embryos. The Carrs chose to use ICSI that first breeding season.

On the first try, several mature and immature oocytes were collected from I Will Be A Good RV in two different procedures. By the end of the process they had two viable embryos. They kept one and one went to the horse’s previous owner. Theirs did not result in a pregnancy but the other did.

The next spring, they tried again, this time on two mares. The first collection harvested numerous oocytes, but none made it to pregnancy.

“We don’t have any babies out of those mares for this year and we’re not happy campers. You pay for the process whether it’s successful or not,” Betty said. “But I still think the process makes sense and I’ll try it again.”

Success rates vary based on the mare, but Kevin Dippert, Ph.D., an internationally recognized equine reproduction expert, says the average success rate is 10-15%. In other words, for every 10 oocytes you recover, only one to two may result in a pregnant recipient. On average, there is a 100% success in recovering at least one oocyte following one aspiration session. There is a 70% success in recovering oocytes from follicles and 70% oocytes mature after incubation. Once injected 35% of oocytes result in embryos and 65% of those embryos result in pregnant recipients.

The focus of ICSI often centers around the mare. However, it also extends the breeding careers for stallions. The process requires less sperm, only one, as compared to other reproductive methods making it ideal for studs with limited semen availability or other fertility issues, according to Dippert.

That’s precisely why Candice Hall and Cory Seebach, Black Creek, British Columbia, chose ICSI for their mare, Made By J (Jolene). The British Columbia couple wanted to breed Jolene to the deceased stallion Invitation Only.

“We were surprised at how successful the process can be,” Hall said “We ended up with seven viable embryos from one procedure and this spring we expect two babies. We are so very excited about this cross.”

On a mission

Highpoint Performance Horses uses ICSI on different mares for different reasons. One mare is the farm’s toughest to get an embryo out of and she is fairly young, but a big-time producer. Another mare is a top producer and it benefits the farm to freeze as many embryos out of her as possible since she is 21 years old this year.

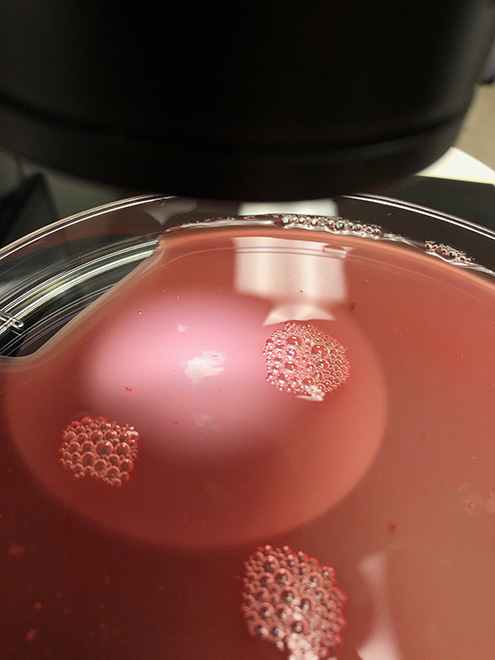

ICSI is based on the collection of viable oocytes residing within individual follicles that develop on a mare’s ovary during the physiologic breeding season, explained Jennifer Hatzel, DVM, ACVS. The assistant professor in equine reproduction works in Colorado State University’s (CSU) Equine Reproduction Lab. Collecting a single oocyte through aspiration of each visible follicle is the first step in the process. An ultrasound probe encased in a long handle is passed through the horse’s vagina and the ovaries are visualized on the ultrasound screen. Then a veterinarian goes in rectally to manipulate the ovary and a needle is passed through the mare’s anterior vagina and into one follicle at a time. Hatzel compares the next step to the turbulent flow in a washing machine. As the follicular fluid is removed, the follicular contents and oocyte is sucked out through the needle and into a sterile collection bottle.

Two types of follicles can be aspirated: mature and immature. Oocytes residing within mature follicles are the easiest to capture with an 80-90% success rate, according to Hatzel. These are the oocytes the mare has matured on her own and under other breeding methods would be ready for fertilization. Immature oocytes must be physically scraped off the ovary wall and have a 50-70% collection success rate, Hatzel said.

“We do not usually aspirate unless we have more than 10 small follicles to go after,” Christensen said. “ICSI can be very costly, so we want the best chance for at least one possible embryo.”

This aspiration process takes about an hour, Dippert explained. Once it’s complete, the mare can either return home or stay at the clinic overnight for observation. It can be repeated 10 to 14 days apart and reduces the number of veterinarian appointments as compared to AI or embryo flushing.

Once the oocytes are out of the mare, one of two things can happen. For those laboratories equipped to perform ICSI, like CSU, the sperm can be injected directly into the egg. However, most private practice veterinarians don’t have a devoted lab for the ICSI procedure or trained embryologists. For these practitioners, once the oocytes are collected, they are placed in a special media and shipped to a laboratory offering the ICISI procedure and embryo culture. Embryos that successfully develop are then transferred into recipient mares, either on site or the embryos can be shipped back and transferred locally.

“The process can be done year-round, except maybe during the winter when mares aren’t producing as many follicles and don’t make it worthwhile,” Dippert said.

However, at Highpoint Performance Horses, Christensen has experienced the most success during the winter months even though the process can be done anytime of the year.

“I’m not sure why, but it’s true,” Christensen said. “A big advantage for us is that ICSI can be done any time of the year.”

Breed, age and seasonality impact the number of follicles available. In Holland specialists are aspirating 30 to 40 follicles out of Warmblood mares as compared to 10 to 20 in US mares. Breed, age and seasonality affect collection rates.

“Certain mares are naturally more prolific than others,” Dippert said. “As with any breeding procedure, it’s the law of averages.”

Hatzel adds that ICSI is a tedious, technical process and she reminds that no breeding method is a guarantee. Even under live cover, the average success rate is only 60-70%.

“There is a natural selection of an oocyte(s) for development into a viable embryo and we don’t know which ones those are so we take as many as we can,” she said. “They call it the miracle of life for a reason.”

Last chance

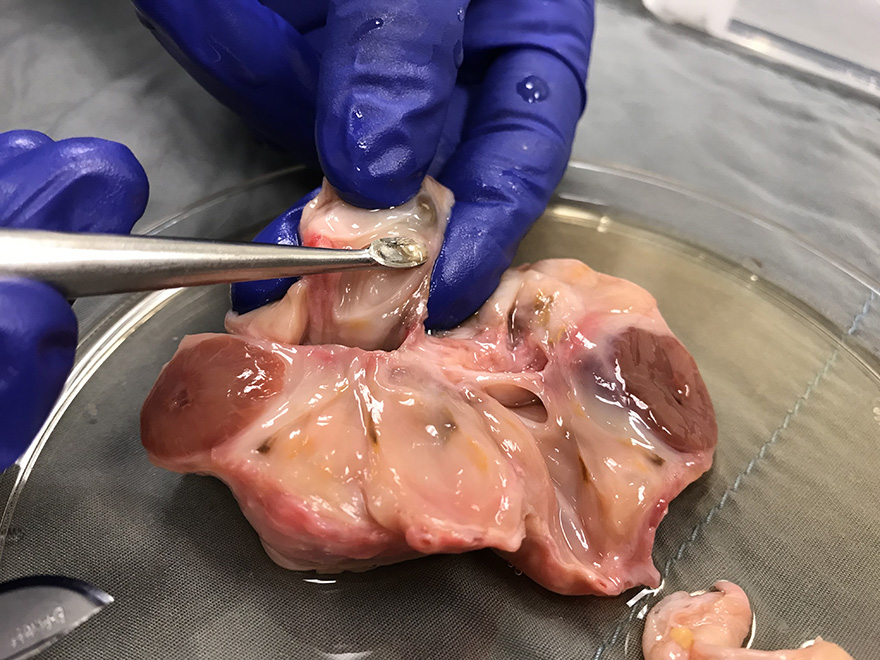

In the of fall 2019, Dippert received a call from a client who knew her well-bred Quarter Horse mare was succumbing to years of chronic lameness. The mare had successfully bred during her peak years, but at 20, laminitis made it difficult for her to stand and the clients knew euthanasia was the next logical step. They knew this day would come at some point so plans were already in mind for the next phase.

“The mare was euthanized at our facility and immediately after her ovaries were harvested and prepared for oocyte recovery,” he explained. “Both ovaries were rinsed with sterile saline, trimmed of any loose tissue and kept at room temperature.”

Over the course of 1.5 hours, Dippert harvested 11 oocytes that were prepared in a media that would preserve the oocytes and they were shipped 1,600 miles to the CSU lab to be injected with sperm. Of the 11 that were harvested, four matured to the point where sperm could be injected. Of those four, two showed signs of cleavage, but only one developed into an embryo that was transferable.

“We all anxiously awaited the results. Could it be that this lone oocyte could actually result in a pregnancy,” he said. “Much to everyone’s delight a healthy developing pregnancy with the presence of a fetus and heartbeat were detected in the recipient mare.”

Harvesting oocytes from deceased mares is more common than you would think. Hatzel says that CSU accepts ovaries. When they arrive, they are treated like an emergency case meaning that staff stays through the night to harvest oocytes before too much time has passed.

“This was a great example of a huge team effort that resulted in a successful pregnancy,” Hatzel said. “Our team views this procedure as one of the most important ways we can contribute during an owner’s darkest hour. If there is a chance to create just one more embryo from that mare, it’s well worth it.”

What to know before signing the dotted line

There’s no guarantee that a viable embryo will be achieved as those fertilized through ICSI are considered a higher risk than those resulting from an embryo flush.

“For an unknown reason to me, ICSI embryos are more likely to make it to a pregnancy, make it to a heartbeat, then be gone on the next check,” Christensen said. “We have had this happen to us a few times even with the best recipient mares lined up and Regumate given religiously to the mare carrying it.”

Breeding in general isn’t inexpensive, however, ICSI may be more expensive than other methods. It’s important to understand the costs involved. It starts with a stud fee. Then there are fees for aspiration, the intracytoplasmic sperm injection and the cost of transferring the embryo into a recipient mare.

“Just making the embryo is very costly and then you have to put that embryo in a recipient mare. Just make sure that you know what you are getting into. I prefer no surprises except the good ones….when they call and let us know how many embryos we have,” Christensen said.

Bailey says that when she looks at the number of foals produced, excluding the embryos that are frozen, each foal has been less expensive to produce for her than following other breeding methods.

“I thought it would cost me $10,000 per foal, but it wasn’t, it was closer to $5,000,” she said. “The last couple years it was costing us $10,000 to $12,000 just to get one foal with flushing. When you spread that out over several foals the cost decreases.”

Bailey says she wished she started using ICSI sooner. Hearing the price, she didn’t think she would be able to afford it, but it has proven to be a more cost-effective method and a way to extend the breeding life of a special mare.

Carr agrees that the process was less costly than she thought. Regardless of the method, there are still fixed costs like stud fees and the expenses of a recip mare. Then if you decide to freeze any embryos, there’s a cost to that as well.

“You pay the same whether you get three or five embryos,” Carr said. “For us it was a good move.”

Hatzel cautions breeders that it may not be worth the investment unless the resulting foal will be worth up to $15,000 or $20,000. The process may cost upwards of $7,000 and may not provide the return on investment.

“Having realistic expectations is key,” she said.

Hatzel also reminds breeders that in human reproduction in vitro methods are a last resort. Couples have already tried less invasive methods, advancing as other attempts fail.

“If someone comes to me and says they want to do this on a young mare, it’s much more in their best interest and the mares’ to start with a less invasive method,” she said.

You must be logged in to post a comment Login